A recurring task of mine is to look at some old calculations, done by some previous engineer whose identity is lost to time and organizational flux, and update them to match current reality. Depending on the state of the spreadsheet, and its lack of documentation, this can also mean going down a rabbit hole of research to find where, exactly, a given equation came from and what all the constants in it represent. This post is the result of one of those journeys, trying to track down the source of a model for depressuring a vessel.

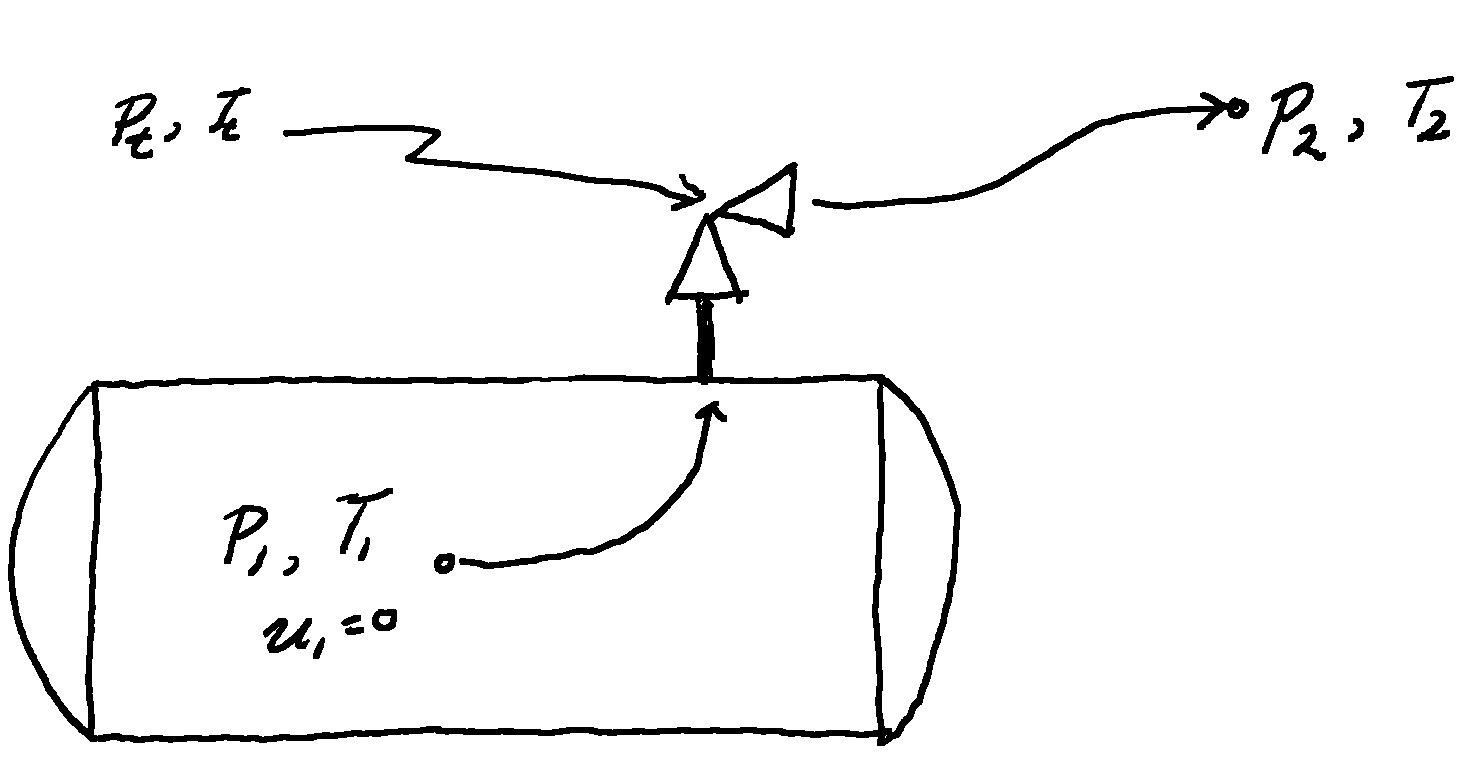

Consider the blowdown of a pressure vessel to a vent stack, where the vessel contains a gas. What we want is the time to fully depressure and the pressure curve (the blowdown curve). As a first approximation we can consider the ideal gas case and examine two limiting behaviours for the vessel: when the walls are perfect insulators (the adiabatic case) and when the walls are perfect conductors of heat (the isothermal case). Furthermore we assume the blowdown is through an isentropic nozzle.

The Adiabatic Case

The adiabatic case is often a good approximation for small vessels and early in the blowdown, when the rate of energy lost from the vessel through the bulk transport of the gas is much higher than any heat gained from the environment.

Starting with a mass balance on the vessel:

\[\frac{dm}{dt} = - w\]where m is the mass inside the vessel and w is the mass flow through the valve. Since the volume of the vessel is a constant, V, we can write the mass balance as

\[V \frac{d \rho}{dt} = - w\]We can perform a change of variables from ρ to P

\[V \left( \frac{\partial \rho}{\partial P} \right)_S \frac{dP}{dt} = - w\]The partial derivative is taken along an isentropic path as the adiabatic expansion within the vessel is isentropic (not because the valve is isentropic).

We can write the mass flow through the nozzle in terms of the theoretical, friction less, mass velocity G, the discharge coefficient $c_D$, and the flow area A.

\[w = c_D A G\]givingBotros, Jungowski, and Weiss, “Models and Methods of Simulating Gas Pipeline Blowdown.”

\[\frac{dP}{dt} = - \frac{c_D A}{V} \left( \frac{\partial P}{\partial \rho} \right)_S G\]Fully Choked Flow

Assuming the flow through the valve is choked, the velocity in the throat is the sonic velocity $a_t$ which, for an ideal gas, is given by

\[a = \sqrt{ {k R T} \over M} = \sqrt{ {k P} \over \rho}\]An ideal gas undergoing an adiabatic expansion from vessel pressure to the pressure in the throat of the valve has the following relationship between density and pressureAny physical chemistry textbook, such as Laidler, Meiser, and Sanctuary, Physical Chemistry, 79 - 81

\[\frac{\rho_t}{\rho} = \left( \frac{P_t}{P} \right)^{\frac{1}{k} }\]and, for choked flow, the pressure ratio is at maximum atTilton, “Fluid and Particle Dynamics,” 6-22 - 6-23.

\[\frac{P_t}{P} = \left( { 2 \over {k+1} } \right)^{\frac{k}{k-1} }\]putting this all together we can write G in terms of vessel conditions $\rho$ and $P$

\[G = \rho_t u_t = \rho_t a_t = \rho_t \sqrt{ {k P_t} \over \rho_t} = \sqrt{k \rho_t P_t}\] \[G = \sqrt{k \rho P} \left( 2 \over {k+1} \right)^{\frac{k+1}{2 \left( k - 1 \right)} }\]From thermodynamics we know

\[\left( \frac{\partial P}{\partial \rho} \right)_S = a^2 = \frac{k P}{\rho}\]and we can put this all together to get

\[\frac{dP}{dt} = - \frac{c_D A}{V} \left( {k P} \over \rho \right) \sqrt{k \rho P} \left( 2 \over {k+1} \right)^{\frac{k+1}{2 \left( k - 1 \right)} }\]At this point, it is standard to introduce a time constant $\tau$

\[\tau = \frac{m_0}{w_0} = \frac{\rho_0 V}{c_D A \sqrt{k \rho_0 P_0} } \left( 2 \over {k+1} \right)^{-\frac{k+1}{2 \left( k - 1 \right)} }\]or, more clearly,

\[\frac{1}{\tau} = \frac{c_D A}{V} \sqrt{ {k P_0} \over \rho_0 } \left( 2 \over {k+1} \right)^{\frac{k+1}{2 \left( k - 1 \right)} }\]Where the subscript 0 indicates the initial conditions in the vessel. This simplifies the expression to

\[\frac{dP}{dt} = -\frac{k}{\tau} P \left( \frac{P}{P_0} \right)^{\frac{k-1}{2k} }\]Which is separable and can be integrated to give (after some rearrangement)

\[\frac{P}{P_0} = \left( 1 + \left( {k-1} \over 2 \right) \frac{t}{\tau} \right)^{\frac{2k}{1-k} }\]and the depressure time is

\[t = \frac{2\tau}{1-k} \left( 1 - \left( \frac{P_a}{P_0} \right)^{\frac{1-k}{2k} } \right)\]Another useful thing to determine is the mass flow rate over time, which can be recovered rather easily recalling

\[w = -\frac{V}{a^2} \frac{dP}{dt} = -\frac{\rho V}{k P} \frac{dP}{dt}\]and

\[\frac{dP}{dt} = -\frac{k}{\tau} P \left( \frac{P}{P_0} \right)^{\frac{k-1}{2k} }\]we get

\[w = \frac{\rho V}{\tau} \left( \frac{P}{P_0} \right)^{\frac{k-1}{2k} } = \frac{\rho_0 V}{\tau} \left( \frac{\rho}{\rho_0} \right) \left( \frac{P}{P_0} \right)^{\frac{k-1}{2k} }\]By recalling the definition of $\tau$ this simplifies to

\[\frac{w}{w_0} = \left( \frac{P}{P_0} \right)^{ {k+1} \over {2k} } = \left( 1 + \left({k-1} \over 2 \right) \frac{t}{\tau} \right)^{\frac{1+k}{1-k} }\]This final model, for mass flow, is the model most often given in process safety references for blowdown rates. This makes some sense as early in a blowdown the observed pressure curve tend to approximate the adiabatic curve. However (foreshadowing) the isothermal curve leads to higher predicted vessel pressures, and generally higher mass flow rates, which might be more conservative depending on the context.

In the Literature

The adiabatic model is the only simple model given in Lees,Lees, Loss Prevention in the Process Industries, 15/44 with the recommendation to use software such as BLOWDOWN to handle more complex, multi phase, mixtures and heat transfer problems. This is also what my older copy of Perry’s gives,Crowl et al., “Process Safety,” 23-57 albeit with a typo.

Perry’s gives the following

\[\frac{w}{w_0} = \left( 1 + \left(\mathbf{k + 1} \over 2 \right) \frac{t}{\tau} \right)^{\frac{1+k}{1-k} }\]Note the sign change, it should be k-1 not k+1, given typical values of k~1.4 this actually a huge difference.

Perry’s only gives the mass flow, so if you wanted the pressure (and the gas density and temperature) you would need to find some other reference. Or do it yourself, it does sketch out how the equation is derived, if you have the spare time to sit down and integrate.

The Complete ODE

There are two obvious limitations to this model: it relies on the gas being well approximated by an ideal gas and that the flow out of the vessel is always choked. The first issue I am not going to deal with right now, the second one I think can be easily dealt with by slightly modifying the governing equations.

\[\frac{dP}{dt} = -\frac{c_D A}{V} a^2 G\]We can solve this numerically given

\[\rho = \rho_0 \left(\frac{P}{P_0}\right)^{\frac{1}{k} }\] \[G = \sqrt{ \rho P \left( {2k} \over {k - 1} \right) \left( \left( \frac{P_t}{P}\right)^{ \frac{2}{k} } - \left( \frac{P_t}{P} \right)^{ \frac{k+1}{k} } \right) }\]function isentropic_mass_flow(P, ρ; k=1.4, Pₐ=101325)

η = max( Pₐ/P, (2/(k+1))^(k/(k-1)))

G² = ρ*P*(2k/(k-1))*( η^(2/k) - η^((k+1)/k) )

G = G² > 0 ? √(G²) : 0

return G

end

function speed_of_sound(P, ρ; k=1.4)

a = √(k*P/ρ)

return a

end

function adiabatic_vessel(P, params, t)

c, A, V, k, ρ₀, P₀, Pₐ = params

ρ = ρ₀*(P/P₀)^(1/k)

a² = speed_of_sound(P, ρ; k=k)^2

G = isentropic_mass_flow(P, ρ; k=k, Pₐ=Pₐ)

return-c*A*a²*G/V

end

with a callback function to terminate the integration once the vessel is fully depressured

function depressured_callback(P, t, integrator; tol=0.001)

c, A, V, k, ρ₀, P₀, Pₐ = integrator.p

return P - (1+tol)*Pₐ

end

A Motivating Example

Just to have a real system to think about, I used to SCUBA dive when I was a teenager and had a few mishaps early on, when I was still figuring things out, accidentally opening the tank valve when the regulator yoke was not fully attached. Blasting air all over the place while I scrambled to shut it off. Typical tanks have capacities ranging from 80 cu. ft. to 100 cu. ft., with working pressures of >3000 psi. That’s a pretty high pressure for a relatively small tank. How fast could the tank blowdown if I opened the valve fully and just sat back and watched?

# Ambient conditions

begin

Pₐ = 101.325e3 # Pa

Tₐ = 288.15 # K

ρₐ = 1.21 # kg/m³

end;

I looked around online and a typical tank with a 80 cu. ft. capacity might have a “water volume” (actual internal volume) of 678 cu. in. (11.11L) and a working pressure of 3000 psi (20.68 MPa). I don’t actually know the flow area of a tank valve, I couldn’t find it easily, so I’m going to guess it’s basically a 1 mm diameter tube when fully open, with a discharge coefficient of 0.85 – all of this could be firmed up better with some real details of the valve. But this is a start.

#Vessel conditions

begin

c = 0.85

D = 0.001 # m

A = 0.25*π*D^2 # m²

V = 0.01111 # m³

P₀ = 20.68e6 # Pa

T₀ = Tₐ

ρ₀ = ρₐ*(P₀/Pₐ) # ideal gas law

k = 1.4

end;

I then set up the differential equation and integrate to get the blowdown curve.

using OrdinaryDiffEq, Plots

begin

params = (c, A, V, k, ρ₀, P₀, Pₐ)

t_span = (0.0, 12.0)

prob = ODEProblem(adiabatic_vessel, P₀, t_span, params)

sol = solve(prob, Tsit5(),

callback=ContinuousCallback(depressured_callback, terminate!))

end;

This model has the tank blowing down pretty fast, in less than 30s. Probably my guess for the valve area is too large. I did just make it up.

Regarding the models themselves, the adiabatic choked model is a very good approximation to the full ODE until the last few fractions of a second, at which point the models diverge. This likely to be true for any high pressure blowdowns, where the vessel pressure starts well above ~2atm, as in that case the majority of the blowdown will be entirely in the choked flow regime.

To play around with this more, I am first going to detour into creating some helper functions and I think this is a natural point to create a struct to contain the vessel parameters.

begin

struct PressureVessel{F <: Number}

c::F

A::F

V::F

k::F

ρ₀::F

P₀::F

Pₐ::F

τ::F

end

PressureVessel(c, A, V, k, ρ₀, P₀, Pₐ, τ) =

PressureVessel(promote(c, A, V, k, ρ₀, P₀, Pₐ, τ)...)

function PressureVessel(c, A, V, k, ρ₀, P₀, Pₐ)

τ = 1/( (c*A/V)*√(k*P₀/ρ₀)*(2/(k+1))^((k+1)/(2*(k-1))) )

return PressureVessel(c, A, V, k, ρ₀, P₀, Pₐ, τ)

end

end;

Where I have added a helper function to ensure all numbers are of the same type, and calculate the value of τ when the PressureVessel type is constructed.

Recreating the results from above, I start with a definition of the vessel

vessel = PressureVessel(c, A, V, k, ρ₀, P₀, Pₐ);

I would like to create some generic functions for the blowdown properties I am interested in: pressure and mass flow rate as functions of time and total blowdown time. To accommodate this I define another type to contain the VesselBlowdown solution.

abstract type Blowdown end

struct AdiabaticBlowdown{S} <: Blowdown

pv::PressureVessel

sol::S

end

Here I add some functions to make a Blowdown object act like an iterator with only a single element. This is absolutely pointless except that I just happen to like being able to generate a vector of results by using the “dot” notation, like so

my_function.(blowdown, time_vector)

where I want it to broadcast over the time_vector.

Base.length(::Blowdown) = 1

Base.iterate(b::Blowdown, state=1) = state > length(b) ? nothing : (b,state+1)

For the simple choked model this is fairly straight forward.

adiabatic_blowdown_choked(vessel::PressureVessel) =

AdiabaticBlowdown(vessel,nothing)

function blowdown_pressure(bd::AdiabaticBlowdown, t)

P₀, k, τ = bd.pv.P₀, bd.pv.k, bd.pv.τ

return P₀*( 1 + 0.5*(k-1)*(t/τ))^((2*k)/(1-k))

end

function blowdown_mass_rate(bd::AdiabaticBlowdown, t)

ρ₀, V, P₀, k, τ = bd.pv.ρ₀, bd.pv.V, bd.pv.P₀, bd.pv.k,

bd.pv.τ

m₀ = ρ₀*V

w₀ = m₀/τ

P = blowdown_pressure(bd, t)

return w₀*(P/P₀)^((k+1)/(2k))

end

function blowdown_time(bd::AdiabaticBlowdown)

P₀, Pₐ, k, τ = bd.pv.P₀, bd.pv.Pₐ, bd.pv.k, bd.pv.τ

return (2τ/(1-k))*(1 - (Pₐ/P₀)^((1-k)/2k))

end

For the full model the initial step is to integrate the differential equation. As a first guess, I calculate the blowdown time for a fully choked blowdown and set the outer-bound for the integration to 10× this. The integrator will terminate when the pressure reaches ambient and thus the last time stored will be the actual blowdown time.

function adiabatic_blowdown_full(vessel::PressureVessel; solver=Tsit5())

# unpack the parameters

c, A, V, k, ρ₀, P₀, Pₐ = vessel.c, vessel.A, vessel.V,

vessel.k, vessel.ρ₀, vessel.P₀,

vessel.Pₐ

params = (c, A, V, k, ρ₀, P₀, Pₐ)

# estimate the time span needed to fully blowdown

τ = vessel.τ

t_bd = (2τ/(1-k))*(1 - (Pₐ/P₀)^((1-k)/2k))

t_span = (0.0, 10t_bd)

# set up the ODEProblem and solve

prob = ODEProblem(adiabatic_vessel, P₀, t_span, params)

sol = solve(prob, solver,

callback=ContinuousCallback(depressured_callback, terminate!))

return AdiabaticBlowdown(vessel,sol)

end

function blowdown_pressure(bd::AdiabaticBlowdown{<:ODESolution}, t)

if t < blowdown_time(bd)

return bd.sol(t)

else

return bd.sol.u[end]

end

end

function blowdown_mass_rate(bd::AdiabaticBlowdown{<:ODESolution}, t)

if t < blowdown_time(bd)

# unpack the parameters

c, A, k, ρ₀, P₀, Pₐ = bd.pv.c, bd.pv.A, bd.pv.k,

bd.pv.ρ₀, bd.pv.P₀, bd.pv.Pₐ

# calculate w = c*A*G

P = blowdown_pressure(bd, t)

ρ = ρ₀*(P/P₀)^(1/k)

G = isentropic_mass_flow(P, ρ; k=k, Pₐ=Pₐ)

return c*A*G

else

return 0.0

end

end

blowdown_time(bd::AdiabaticBlowdown{<:ODESolution}) =

bd.sol.t[end]

At this point I’ve built up enough machinery that playing around with all sorts of variations to the original case become quite simple. As an example, I look at the same air tank but pressured to 1.5 atm instead.

test_vessel = PressureVessel(c, A, V, k, ρ₀, 1.5Pₐ, Pₐ);

Now it is clear that the fully choked model model isn’t working well, it predicts a blowdown time of 11.68s whereas numerically solving the ODE gives an answer of 20.49s, a 75.0% greater predicted blowdown.

That said…I’m being a little coy about something: the full ODE predicts that the vessel will never blowdown. The pressure will get closer and closer to ambient but never get there. This is because G, for non-choked flow, asymptotically approaches zero as the vessel pressure approaches ambient pressure. How you define blowdown time is really a function of how close to ambient is close enough. Even if I set the tolerance in the depressured_callback function, which terminates the integration once the integrator is within tolerance of the ambient pressure, to zero it would, in reality, simply terminate at the default numerical precision of DifferentialEquations.jl. In this case I’ve said “within 0.1% of ambient is close enough,” but that’s totally arbitrary.

The Isothermal Case

The other limiting case worth exploring is the isothermal case, which is equivalent to the vessel having perfectly conductive walls and remaining always at thermal equilibrium with the environment. This is often a good approximation for large vessels where the blowdown rate is small relative to the thermal mass of the gas in the vessel.

Recalling, for the adiabatic case, we had the following

\[\frac{dP}{dt} = - \frac{c_D A}{V} \left( \frac{\partial P}{\partial \rho} \right)_S G\]For the isothermal case the vessel is being depressured along an isothermal path (not an isentropic path) and so we substitute the appropriate partial derivativeBotros, Jungowski, and Weiss, “Models and Methods of Simulating Gas Pipeline Blowdown.”

\[\frac{dP}{dt} = - \frac{c_D A}{V} \left( \frac{\partial P}{\partial \rho} \right)_T G\]Fully Choked Flow

As before, the blowdown is through an isentropic nozzle and we assume that flow is choked

\[G = \sqrt{k \rho P} \left( \frac{2}{k+1} \right)^{\frac{k+1}{2 \left( k-1 \right)} } = \rho \sqrt{ {k P} \over \rho} \left( \frac{2}{k+1} \right)^{\frac{k+1}{2 \left( k-1 \right)} }\]From thermodynamics we can write the partial derivative as

\[\left( \frac{\partial P}{\partial \rho} \right)_T = \frac{a^2}{k} = \frac{P}{\rho}\]Thus

\[\frac{dP}{dt} = - \frac{c_D A}{V} \frac{P}{\rho} \rho \sqrt{ {k P} \over \rho} \left( \frac{2}{k+1} \right)^{\frac{k+1}{2 \left( k-1 \right)} }\]where the densities, $\rho$, can be cancelled and, since the vessel is isothermal (i.e. $\frac{P}{\rho}$ is a constant), the various constants can be collected to give

\[\frac{dP}{dt} = -\frac{P}{\tau}\]Where $\tau$ is as defined for the adiabatic case. This can easily be integrated to give

\[\frac{P}{P_0} = \exp \left( \frac{-t}{\tau} \right)\]it also follows, from the ideal gas law, that

\[\frac{\rho}{\rho_0} = \exp \left( \frac{-t}{\tau} \right)\]and

\[\frac{w}{w_0} = \exp \left( \frac{-t}{\tau} \right)\]This can also be rearranged to give the blowdown timeN.B. the $\log \left( \dots \right)$ is the natural log, this matches the convention used in julia

\[t = \tau \log \left( \frac{P_0}{P_a} \right)\]In the Literature

This is the equation seen most often in references for estimating blowdown time for pipelines and compressor systems. It is also what is going on under the hood with many online calculators for vessel blowdown times. Though, in my experience, this is not always well documented and a modified form is often presented.

The time constant, $\tau$, can be broken up to look like this

\[\tau = \frac{V}{c_D A} \sqrt{\frac{M}{M_{air} Z_0 T_0} } \sqrt{\frac{M_{air} }{kR} } \left( 2 \over {k+1} \right)^{\frac{-1}{2} \frac{k+1}{k-1} }\]Where we have made the substitution $Z_0 R T_0$ for $R T_0$ to account for non-ideal behaviour. If the gas has a value of k ~ 1.4, we can write

\[\tau = \mathrm{const} \frac{V}{c_D A} \sqrt{ \frac{SG}{Z_0 T_0} }\]Where the constant is calculated entirely from the properties of air. Generally, I have found, few references describe where this constant comes from and in particular that it depends implicitly on a particular value for k. It also often has unit conversions absorbed into it, for exampleCampbell, Gas Conditioning and Processing, 29; VANEC, “Pressure Volume-Blowdown Time Calculation,”

\[t = 5.5 \frac{V}{c_D A} \sqrt{ \frac{SG}{Z_0 T_0} } \log \left( \frac{P_0}{P_a} \right)\]with the units

- Blowdown time, t, in seconds

- Vessel volume, V, in cubic feet

- Valve flow area, A, in square inches

- Initial temperature, $T_0$, in Rankine

- Initial pressure, $P_0$, in psia

- Ambient pressure, $P_a$, in psia

I have also found a few sources that leave the value of the constant as a mystery for the user to puzzle out.Temizel et al., Formulas and Calculations for Petroleum Engineering, 262; Engineers Edge, “Blowdown Time in Unsteady Gas Flow Calculator and Equation.” I was honestly surprised at the quality of the results when I first googled this and looked it up in Knovel. The highest ranked results, at the time, were cryptic to the point of uselessness or included obvious mistakes (several referred to t as the “interstitial velocity” with units of cm/s, an obvious misprint being blindly recopied in several places, including some e-books on Knovel where one would hope the quality control would be better). There are a few places with useful derivationsWheeler, “Tank Blowdown Math.”; Botros, Jungowski, and Weiss, “Models and Methods of Simulating Gas Pipeline Blowdown.”; Botros and Van Hardeveld, Pipeline Pumping and Compression Systems, 447; Saad, Compressible Fluid Flow, 98-103, to list but a few. but I think a good starting point is the Tank Blowdown Math set of notes. It is pretty straight forward and does not require a lot of prior knowledge of the partial derivatives of various thermodynamic state variables.

I personally would not bother with the models that pre-calculate the constant for you. We no longer live in the age of slide-rules. The blowdown time equation for fully choked flow is well within the capabilities of excel or any competent person with a scientific calculator. I think it is easier to justify and explain, will be a better model for gases where k is not 1.4, and allows one to incorporate small levels of non-ideality through the isentropic expansion factor n.

The isothermal fully-choked model can be implemented building on the types already created, by first creating an IsothermalBlowdown type and associated blowdown functions

struct IsothermalBlowdown{S} <: Blowdown

pv::PressureVessel

sol::S

end

isothermal_blowdown_choked(vessel::PressureVessel) =

IsothermalBlowdown(vessel,nothing)

function blowdown_pressure(bd::IsothermalBlowdown, t)

P₀, τ = bd.pv.P₀, bd.pv.τ

return P₀*exp(-t/τ)

end

function blowdown_mass_rate(bd::IsothermalBlowdown, t)

ρ₀, V, τ = bd.pv.ρ₀, bd.pv.V, bd.pv.τ

m₀ = ρ₀*V

w₀ = m₀/τ

return w₀*exp(-t/τ)

end

blowdown_time(bd::IsothermalBlowdown) =

bd.pv.τ*log(bd.pv.P₀/bd.pv.Pₐ)

In a similar vein as the adiabatic case, the requirement for fully choked flow can be relaxed and the ODE integrated numerically instead, starting with the system

\[\frac{dP}{dt} = -\frac{c_D A}{V} \frac{a^2}{k} G\]We can solve this numerically given that, for an isothermal system, the density is given by

\[\rho = \rho_0 \left(\frac{P}{P_0}\right)\]and using the definition of G given in the adiabatic case.

function isothermal_vessel(P, params, t)

c, A, V, k, ρ₀, P₀, Pₐ = params

ρ = ρ₀*(P/P₀)

a² = speed_of_sound(P, ρ; k=k)^2

G = isentropic_mass_flow(P, ρ; k=k, Pₐ=Pₐ)

return-c*A*a²*G/(k*V)

end

function isothermal_blowdown_full(vessel::PressureVessel; solver=Tsit5())

# unpack the parameters

c, A, V, k, ρ₀, P₀, Pₐ = vessel.c, vessel.A, vessel.V,

vessel.k, vessel.ρ₀, vessel.P₀,

vessel.Pₐ

params = (c, A, V, k, ρ₀, P₀, Pₐ)

# estimate the time span needed to fully blowdown

τ = vessel.τ

t_bd = τ*log(P₀/Pₐ)

t_span = (0.0, 10t_bd)

# set up the ODEProblem and solve

prob = ODEProblem(isothermal_vessel, P₀, t_span, params)

sol = solve(prob, solver,

callback=ContinuousCallback(depressured_callback, terminate!))

return IsothermalBlowdown(vessel,sol)

end

function blowdown_pressure(bd::IsothermalBlowdown{<:ODESolution}, t)

if t < blowdown_time(bd)

return bd.sol(t)

else

return bd.sol.u[end]

end

end

function blowdown_mass_rate(bd::IsothermalBlowdown{<:ODESolution}, t)

if t < blowdown_time(bd)

# unpack the parameters

c, A, k, ρ₀, P₀, Pₐ = bd.pv.c, bd.pv.A, bd.pv.k,

bd.pv.ρ₀, bd.pv.P₀, bd.pv.Pₐ

# calculate w = c*A*G

P = blowdown_pressure(bd, t)

ρ = ρ₀*(P/P₀)

G = isentropic_mass_flow(P, ρ; k=k, Pₐ=Pₐ)

return c*A*G

else

return 0.0

end

end

blowdown_time(bd::IsothermalBlowdown{<:ODESolution}) =

bd.sol.t[end]

It is a similar story to the adiabatic case: for systems with a high initial pressure, the flow out of the valve is fully choked for almost the entire blowdown. It is only in the final fraction of a second that the full ODE system deviates from the model that assumes flow is choked all the time.

In most practical situations, the difference would likely be swamped by two much greater problems with these models:

- the gases are assumed be ideal with constant k

- the vessel is perfectly isothermal (or adiabatic)

Both of these assumptions will have a much greater impact on how well the model fits observed blowdowns than the slight deviation at the end of the blowdown due to non-choked flow.

Comparing Blowdown Models

I think it might be simpler to visualize when the choked flow blowdown models will fall down by looking at the high pressure blowdown, the original example, versus the low pressure blowdown in dimensionless form. In this form, the choked flow blowdown curves (both adiabatic and isothermal) only depend on k. They are in fact the exact same curve. All that has changed is where along the curve the blowdown terminates.

In the high pressure case the blowdown terminates much closer to $\frac{P}{P_0}=0$ and most of the curve is fully choked.

In the low pressure case the blowdown terminates at a much steeper part of the blowdown curve and the departure for non-choking flow is much more apparent.

It is not immediately clear to me why the adiabatic case is all over the standard references for process safety, and the isothermal model is not. If what you care about is the pressure sustained within a vessel, the mass flow rate emitted through a blowdown stack or vent, and the duration of the blowdown, it is almost always more conservative to use the isothermal case. The isothermal (fully choked) model is also just easier to calculate, being just $\exp \left( \frac{-t}{\tau} \right)$.

The adiabatic case will give a better sense of how temperature changes within the vessel. I’ve largely left it out, but adiabatic blowdown does lead to a significant temperature drop and this cryogenic cooling can be a process hazard on its own. The gas exiting, and the vessel walls themselves, will get quite cold. Anyone who has gone camping in more marginal weather and watched a one-pound propane cylinder develop frost on the outside while cooking has seen this effect in action.This is also why butane cylinders are often not a good idea for early spring camping (in Canada), the cooling effect is strong enough to cause the butane inside to liquefy and the stove won’t work very well. But actually calculating the vessel temperature is almost entirely ignored in blowdown calculations for ideal gases, in my experience.

The isothermal model, in my review of the literature, appeared to be more commonly used in operational contexts, such as estimating the time required to blowdown a system through a blowdown vent. In this case it is likely to be the conservative answer. The two curves do cross at high $\frac{t}{\tau}$ and so it is not always the case that the isothermal model is more conservative. Something worth noting.

Final Thoughts

I deliberately set up the ODEs such that there is a clear path to implementing a real gas model through an equation of state. All that really needs to be done is to create functions for these three steps:

- the speed of sound

- the density as a function of pressure, either along an isentropic path (in the adiabatic case) or along an isothermal path

- the isentropic mass velocity, G

Plugging those into the relevant steps in the adiabatic_vessel and isothermal_vessel functions changes from the ideal gas case to the real gas case. The rest of the code remains the same and operates unchanged.

In this case I think solving the full ODE for the ideal gas case alone is probably not worth the effort for most cases. The error in assuming an ideal gas, or in assuming one of the limiting heat transfer cases, is probably far larger than the error in assuming fully choked flow for all but the few cases that are near atmospheric pressure. If you are going to be estimating the blowdown for a real gas, then that’s different. If you are going to the hassle of setting up and solving the ODE, might as well have as few unnecessary assumptions as you can get away with. It really isn’t any more person effort, at that point, just more computer effort, and when the calculations happen in less than a second, how much less than a second is of little practical importance.

For a complete listing of code used to generate data and figures, please see the corresponding pluto notebook

References

- Botros, Kamal K., and Thomas Van Hardeveld. Pipeline Pumping and Compression Systems - A Practical Approach. 3rd ed. New York: ASME Press. 2018

- Campbell, John M. Gas Conditioning and Processing. vol 2. Tulsa, OK: John M. Campbell & Co. 1992.

- Crowl, Daniel A., Lawrence G. Britton, Walter L. Frank, Stanley Grossel, Dennis Hendershot, W. G. High, Robert W. Johnson et al. "Process Safety." in Green, Perry’s Chemical Engineers’ Handbook.

- Engineers Edge. "Blowdown Time in Unsteady Gas Flow Calculator and Equation." accessed January 13, 2025 [ url ]

- Green, Don W., ed. Perry’s Chemical Engineers’ Handbook. 8th ed. New York: McGraw Hill, 2008.

- Laidler, Keith J., John H. Meiser, and Bryan C. Sanctuary. Physical Chemistry. 4th ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 2003.

- Lees, Frank P. Loss Prevention in the Process Industries. 2nd ed. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1996.

- Saad, Michel A. Compressible Fluid Flow. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentiss-Hall. 1985

- Temizel, Cenk, Tayfun Tuna, Mehmet Melik Oskay, and Luigi Saputelli. Formulas and Calculations for Petroleum Engineering. Cambridge, MA: Gulf Professional Publishing. 2019.

- Tilton, James N. "Fluid and Particle Dynamics." in Green, Perry’s Chemical Engineers’ Handbook.

- VANEC. "Pressure Volume-Blowdown Time Calculation." accessed January 11, 2025 [ url ]

- Wheeler, Dean R. "Tank Blowdown Math." March 13, 2019 [ url ]

Comments